- Главная

- Разное

- Образование

- Спорт

- Естествознание

- Природоведение

- Религиоведение

- Французский язык

- Черчение

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, фоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

Презентация, доклад по теме Magna Carta к курсу страноведение

Содержание

- 1. Презентация по теме Magna Carta к курсу страноведение

- 2. John's brother, Richard I, caused problems John's

- 3. King John was unpopular John collected taxes,

- 4. Rebellions and Magna Carta The reign of

- 5. The reign of King John was a

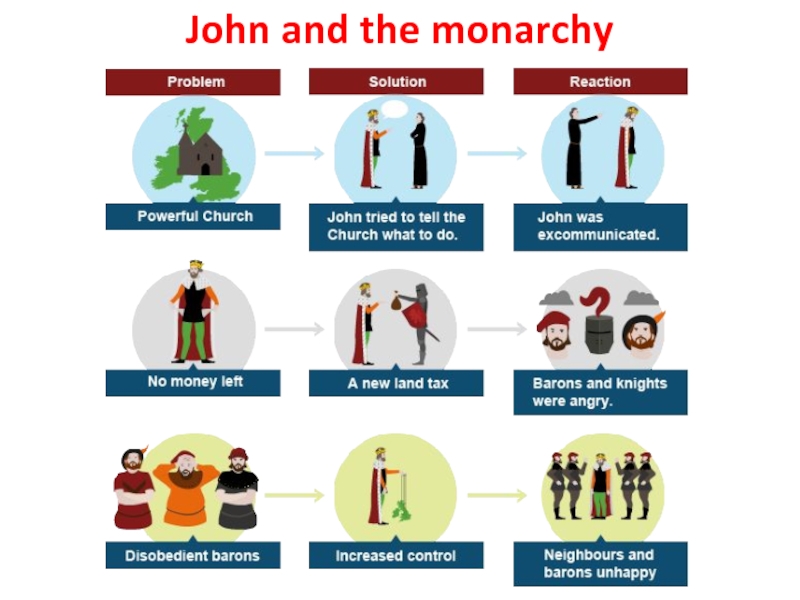

- 6. John and the monarchy

- 7. When John became king after his brother,

- 8. During John's reign, he tried to strengthen

- 9. John's actions angered many people:Barons and knights would

- 10. Creation of Magna Carta

- 11. In 1204 Philip invaded Normandy and drove

- 12. Magna Carta Magna Carta contained 63 promises

- 13. Consequences of Magna Carta Although Magna Carta

- 14. a £100 limit on the tax barons

- 15. Three of the promises of Magna Carta

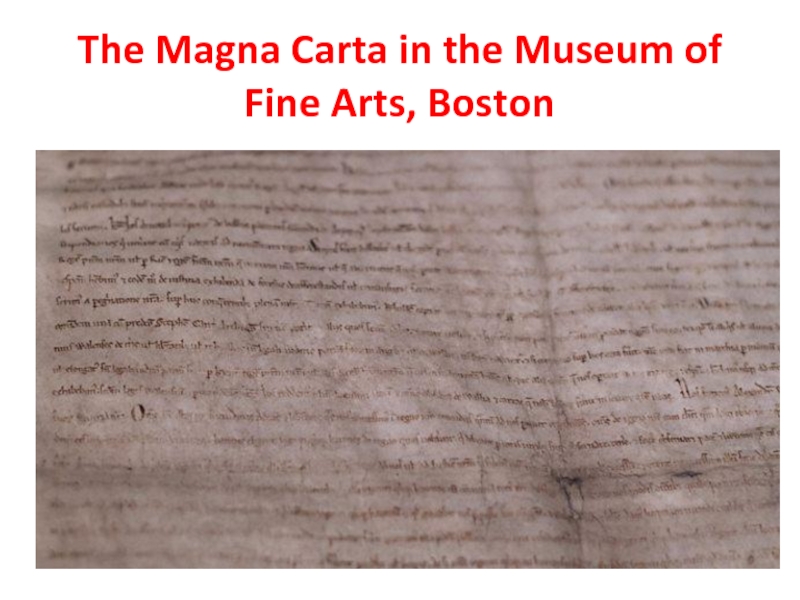

- 16. The Magna Carta in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- 17. Historical interpretations of Magna Carta In the

John's brother, Richard I, caused problems John's brother, Richard I, had spent all the money in the treasury on his Crusades. The Crusades were a series of military campaigns over hundreds of years to take sole control of Jerusalem

Слайд 2John's brother, Richard I, caused problems

John's brother, Richard I, had spent

all the money in the treasury on his Crusades. The Crusades were a series of military campaigns over hundreds of years to take sole control of Jerusalem for the Christian faith. Richard also let the barons become too powerful whilst he was in the Holy Land.

Слайд 3King John was unpopular

John collected taxes, modernised the government and exerted

his power over the Church, Scotland and Ireland. This made him unpopular with the barons. In 1201-2, helped by King Philip of France, the lords of Lusignan, a powerful alliance of French nobles, rebelled against John. John mounted a huge campaign to re-conquer Normandy, but was badly defeated at the Battle of Bouvines (1214). John was forced to pay the huge sum of 20,000 marks and concede some lands in France in order for King Philip to recognise him as the heir to Richard I. John was exposed as diplomatically weak.

Слайд 4Rebellions and Magna Carta

The reign of King John shows what often

happened in the Middle Ages when a monarch lost a war – his authority was completely undermined. The barons rebelled and, on 15 June 1215, they forced John to agree to Magna Carta (The Great Charter) - a set of demands by which the barons tried to limit the power of the king to their advantage.

Слайд 5The reign of King John was a turning point in the

history of England's government. The barons – successfully – had said 'no' to the king, and made him do as they wanted. The charter only spoke about freemenand not the majority of people who were peasants. No monarch of England ever had unrestricted, or 'absolute', power again and within a century England saw the beginnings of Parliament.

Слайд 7When John became king after his brother, Richard I, died in

France, he inherited a weakened monarchy:

Richard had spent the money in the royal treasury to pay for his Crusades and, when he was captured, for his ransom.

Richard only spent six months of his 10-year reign in England. The rest of the time the kingdom was ruled by officials, such as clerks and court advisers, so the barons got used to doing as they pleased.

Слайд 8During John's reign, he tried to strengthen the monarchy:

He collected a

new land tax from the knights and the barons.

He modernised the government and kept good records.

He tried to force the Church to accept his candidate for Archbishop of Canterbury.

He increased his control over Ireland and Wales, and built up his forces in northern England. The King of Scotland signed a peace treaty with John.

He modernised the government and kept good records.

He tried to force the Church to accept his candidate for Archbishop of Canterbury.

He increased his control over Ireland and Wales, and built up his forces in northern England. The King of Scotland signed a peace treaty with John.

Слайд 9John's actions angered many people:

Barons and knights would have been angry at

having to pay taxes for wars John lost.

Both officials and barons would have resented King John taking away their power. Everybody saw it as an attack on their freedom.

In 1201-2, helped by King Philip of France, the Lords of Lusignan began a rebellion against John, their feudal lord.

The Church didn't want to be told what to do. As a result, Pope Innocent III stopped English priests from holding religious services, known as the 'interdict', and excommunicated King John between 1209 and 1213. This meant the loss of support from the very powerful Pope.

The Irish, Welsh and Scots all hated the power John had in their countries.

Both officials and barons would have resented King John taking away their power. Everybody saw it as an attack on their freedom.

In 1201-2, helped by King Philip of France, the Lords of Lusignan began a rebellion against John, their feudal lord.

The Church didn't want to be told what to do. As a result, Pope Innocent III stopped English priests from holding religious services, known as the 'interdict', and excommunicated King John between 1209 and 1213. This meant the loss of support from the very powerful Pope.

The Irish, Welsh and Scots all hated the power John had in their countries.

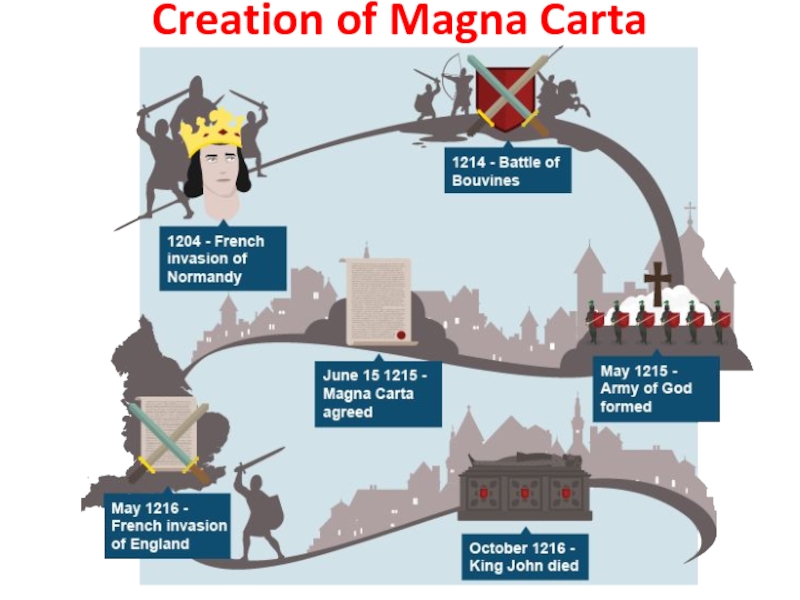

Слайд 11In 1204 Philip invaded Normandy and drove the English out.

In 1214

John mounted a huge campaign to reconquer Normandy, but was badly defeated at the Battle of Bouvines.

John had levied a tax from the barons to pay for his campaign in Normandy. After his defeat at Bouvines he asked the barons for more money for another campaign.

They refused. In May 1215, 40 barons renounced their feudal ties to the king. With French and Scottish support, they formed an army (called 'the Army of God') and on 17 May they captured London.

John had no alternative but to negotiate. He met the rebels at Runnymede, near London, on 15 June 1215, and agreed to Magna Carta.

John had levied a tax from the barons to pay for his campaign in Normandy. After his defeat at Bouvines he asked the barons for more money for another campaign.

They refused. In May 1215, 40 barons renounced their feudal ties to the king. With French and Scottish support, they formed an army (called 'the Army of God') and on 17 May they captured London.

John had no alternative but to negotiate. He met the rebels at Runnymede, near London, on 15 June 1215, and agreed to Magna Carta.

Слайд 12Magna Carta

Magna Carta contained 63 promises about what the king could

and couldn't do. It also set up a Council of 25 barons to make sure John kept his promises.

This was a direct attack on John's royal authority, and as soon as he could, John asked the Pope for permission to ignore Magna Carta – on the grounds that he had been forced to sign it.

John's rejection of Magna Carta caused another rebellion by the barons. The French invaded with support from Scotland and the barons.

In October 1216, retreating from the French, John lost all his supplies and treasure trying to cross the Wash, a bay and estuary between East Anglia and Lincolnshire. He was already ill at this time and died shortly afterwards.

This was a direct attack on John's royal authority, and as soon as he could, John asked the Pope for permission to ignore Magna Carta – on the grounds that he had been forced to sign it.

John's rejection of Magna Carta caused another rebellion by the barons. The French invaded with support from Scotland and the barons.

In October 1216, retreating from the French, John lost all his supplies and treasure trying to cross the Wash, a bay and estuary between East Anglia and Lincolnshire. He was already ill at this time and died shortly afterwards.

Слайд 13Consequences of Magna Carta

Although Magna Carta was not the declaration of human

rights it was later claimed to be, it was the first time a set of rules had been written down for the king. In the 17th century, British lawyers were to use it to resist Charles I's attempt to increase his power.

Слайд 14a £100 limit on the tax barons had to pay to

inherit their lands

the king could not sell or deny justice to anyone

the royal forests were to be reduced in size

an heir could not be made to marry someone of a lower social class

foreign knights had to be deported

no-one could be arrested on the accusation of a woman

the king could not sell or deny justice to anyone

the royal forests were to be reduced in size

an heir could not be made to marry someone of a lower social class

foreign knights had to be deported

no-one could be arrested on the accusation of a woman

Слайд 15Three of the promises of Magna Carta remain in force today:

1.

That the English Church shall be free from royal interference.

13. To respect the rights and freedoms of the City of London and other towns and ports.

39. That no freeman shall be arrested or imprisoned without a proper trial by a jury of peers.

However, the power of the king had been permanently damaged, and no king of England was ever again unrestricted or 'absolute'. Within half a century, England had a parliament to represent the wishes of the barons to the king.

13. To respect the rights and freedoms of the City of London and other towns and ports.

39. That no freeman shall be arrested or imprisoned without a proper trial by a jury of peers.

However, the power of the king had been permanently damaged, and no king of England was ever again unrestricted or 'absolute'. Within half a century, England had a parliament to represent the wishes of the barons to the king.

Слайд 17Historical interpretations of Magna Carta

In the 17th century, the lawyer Edward Coke used

Magna Carta to oppose Charles I's demands for tax to pay for his foreign wars. Coke claimed that Magna Carta guaranteed specific freedoms to Englishmen, including no taxation without the consent of Parliament and no imprisonment without a trial.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, British historians (the 'Whig' historians) saw it as the basis of English democracy.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, British historians (the 'Whig' historians) saw it as the basis of English democracy.